The Polish Church is in crisis. This crisis has many symptoms, not least the growing evidence of sexual crimes committed by the clergy. This particular problem is aggravated by the unacceptable and despicable treatment of such evidence by the Church, which for years covered up the abuse and simply transferred the perpetrators from one parish to another. None of the bishops seem to have given any thought to the actual victims, ignoring their suffering and refusing to do anything to prevent further abuse. Rather, they chose to protect the perpetrators and the “good reputation” of the Church.

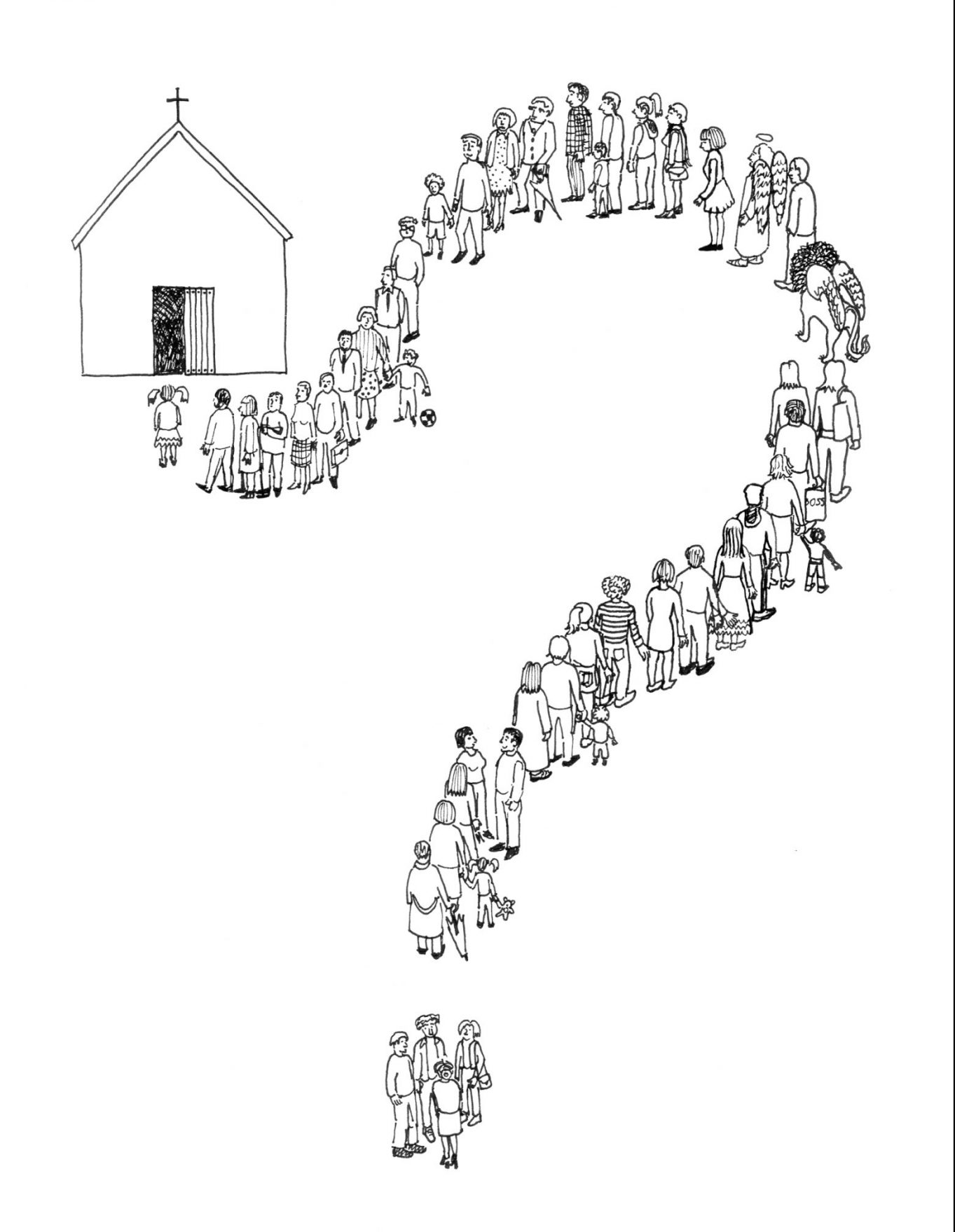

The sexual abuse crisis engulfed Catholicism worldwide and remains its most serious tragedy given the suffering caused. But the crisis of the Polish Church has other symptoms too. Many members feel alienated from the community when Polish bishops explicitly favor the ruling political party and propagate political views from the pulpit. In doing so they even defy Pope Francis, as if the Church here was a separate national institution. In fact, despite the protests from many lay members, the Polish clergy allow radical nationalist groups to organize official pilgrimages, one of which featured priest Roman Kneblewski declaring himself a “Polish nationalist” during the sermon. Churchgoers also oppose the continued marginalization of women, who were again barred from participating in the most recent synod while lay men were not. Other social groups are not just excluded but openly vilified: some in the clergy blame sexual abuse on what they call a “homolobby” and frequently conjure up stories that harm the queer community. Given this hardly exhaustive list of the Church’s deadly sins, we are not surprised that local parishes function more like administrative units than mutual support communities. Those Catholics who are not angry often simply do not care.

One could argue that those problems are caused by a few rotten eggs and that the Church should not be blamed for their sins. There is some truth in such arguments. The rotten eggs, such as Kneblewski or the ex-priest Jacek Międlar, may be loud and visible but the Polish episcopate did openly speak out against nationalism (in 2017, they published a document “The Christian shape of patriotism,” in which they stated that “national egoism, nationalism, which cultivates a sense of superiority and rejects other national communities as well as the human community” is “not Christian.”) Acknowledging this, we should nevertheless also recognize that many of the problems listed above are systemic, particularly the widespread sexual abuse. The perpetrators of sexual crimes spent years in safety knowing full well that no punishment awaited them. Their superiors simply transferred them to one parish after another and swept their crimes under the rug. The victims received no support, whether from the clergy or, even more regrettably, from other members of the Church.

Change is happening but far too slowly. The Church does too little to address its past or face the challenges of the present. The Catholic authorities in Poland remain passive and inept when faced with the myriad symptoms of the crisis.

This failure to act is both a cause and an effect of the systemic problem underlying this crisis. There are structural mechanisms which ensure that evil reproduces itself. Abuse of power, clericalism, silencing of victims, discrimination against sexual minorities and women, all of those evils are not merely a result of the behavior of individual priests or lay members. On the contrary, they are our issues as a community. And they affect not just the Polish Church, but Catholicism worldwide, even though the symptoms of the crisis differ depending on local circumstances.

We are thus all implicated in this crisis. Our entire community, even if often unwittingly, participates in preserving the mechanisms that permit the plague of sin to persist. Therefore, we must be bold enough to “accept that the Church as a community includes ‘structures of evil’,” as Bishop Heiner Wilmer urged us in an interview for the “Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger.”

But once we acknowledge this hard truth, what then? What should we do if our community, regardless of the good it creates, also so frequently fails to address evil and even actively contributes to its spread? Should we not simply abandon such a community?

***

Many in the Polish Church ask themselves this question. The answer is far from obvious as one can adopt several strategies when faced with the crisis. Indeed, one of those strategies is to leave the community of the Church, even if one does not lose their faith. Another is to keep receiving sacraments and engaging in religious rites, while staying away from the life of the broader community. Then there is the third way. One can accept the notion that there are parts of the Church that are not pervaded by evil, actively participate in the community, especially at a local level, choose to only interact with the “good priests.” We should take a closer look at this third way, as many of us who are more critical towards the Church community follow this path.

Indeed, we cannot conclude that all elements of the Church are bad, even if the total sum of the parts fails so often. Many wise, thoughtful priests co-create communities of the faithful that enrich lives and help guide people towards good. Many congregations include members who truly experience solidarity and unity that brings them closer to God. Many bishops resolutely follow Pope Francis and his brand of socially-oriented Catholicism on questions ranging from the environment (such as the Silesian bishops who spoke about air pollution) to refugees (such as Bishop Krzysztof Zadarko or Archbishop Wojciech Polak.) Propelled by such individuals, the Polish Church does contribute to good causes and does help make the world a better place.

But what about the evil that exists within the Church itself? There are reasons to remain hopeful that the Polish clergy will confront and remedy the suffering caused by sexual abuse. For instance, there is the Opole bishop Andrzej Czaja, who meets with and listens to the victims and who openly shared his feelings after watching “Kler,” a documentary detailing the crimes of the clergy in Poland. “One of the most important scenes was a hearing where one of the victims detailed the abuse he experienced in front of a group of priests and bishops who sat there unmoved and indifferent. At some point this man stood up and simply said, ‘you people, what are you doing, what are you doing?!’ . . . It was as if, through this film, God Himself was calling us, the clergy, and especially those of us who lost the way, to say, ‘people, what are you doing?!’” There are other individual bishops who give us hope, for instance Józef Guzdka, Piotr Libera and Romuald Kamiński, all of whom not only apologized to the victims but made available the information about the cases they personally became aware of.

Those words and gestures do show that the Catholic community in Poland is not passive in face of this crisis and that there are individual priests we can, so to speak, “count on.” But those words and gestures do not solve the problem. Structurally, the Church remains unchanged. The suffering has been inflicted. The words of few priests who speak out against evil are drowned out in the sea of problematic voices or, worse, in the devastating silence. This is simply not enough.

The individuals who speak out and those who ignore abuse all belong to the Church. As a Catholic, thus universal, collective, the Church necessarily encompasses all of them and it cannot be divided into disparate parishes with their own distinct sub-communities. Hence, as members of this one community we have to take responsibility for it as a whole. And while we do not want to bestow judgement upon individuals who choose one of the three aforementioned strategies in response to the crisis of the Church, we want to propose a fourth one. We at the Kontakt Magazine choose to consciously belong to this one Church and to work to make it better.

***

We are convinced that being a part of the Church community is worthwhile. We believe that another Church is possible. And that it is our duty to fight for change. When we speak of “another” Church, we do not reject the one that exists, we do not want to replace it with a new institution. We have faith in the continuity of its teachings and traditions. Still, we want the Church community to reflect critically on what it has become, to recognize its sins, to take responsibility for its failures, and to strive for change. And when we speak of community, we mean the entire collective and not just the clergy. Lay Catholics must participate in making change because “we, though many, are one body in Christ” (Romans 12:5). We cannot forget that “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Matthew 25:40) and thus that any suffering caused by some in the Church matters to all of us. It is the duty of our entire community to speak out against the perpetrators of abuse because we are, in fact, one body. Whomever the Church hurts, whether it be children or adults, our compatriots or foreigners, LGBTQ+ or straight and cisgender persons, we must act. Because God called His people – the people of the Church – to worship and to love and never to hurt.

Many have been hurt. Remembering this, we do not lose faith that our commitment to the Church will bring fruit. History shows us that change is possible, even if it seems that some aspects of the Church are beyond reform. After all, over the two millennia the Church transformed while never forgetting that the essence of its teachings is rooted in the source of the truth, the Holy Bible. There was a time when the ecumenical movement, today such a vital part of the Church, would not have been accepted. But in 1965, the Catholic-Orthodox Joint Declaration withdrew the exchange of excommunications between the Holy See and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople that undergirded the Great Schism 900 years prior. This change was made possible in large part due to the tireless work of individual Catholics who had themselves begun the dialogue with members of other faiths. And the change in the official position of the Vatican, in turn, convinced the wider Catholic community that the ecumenical movement was in fact a true expression of the love that the Church was called to spread. For centuries, religious difference caused hatred and violence to spread. But a combination of bottom-up efforts and top-down changes ensured we now live in a world where such hatred and violence has no place.

Reconciliation between world religions showcased that change, even of such magnitude and after such a long time, is possible. In the 1960s such a shift may have seemed unimaginable to many Catholics. Hopefully, we will not need 900 years to change other important aspects of our community. And such hope seems justified given that change has been happening a lot faster in the past decades than in the centuries prior.

We have reasons to be hopeful but it does not mean that we are having an easy time working towards change. Transforming the Church from within requires us to make individual decisions and take up challenges that often prove difficult. Therefore, we cannot judge anyone who chooses to leave the community, especially not those whom the community hurt. But precisely for this reason we should appreciate even more those who stay. We see wonderful testimonies of faith and dedication all around us: the members of the “Wiara i Tęcza” (“Faith and Rainbow”) group, which gathers LGBTQ+ believers; all the victims of child abuse who remain in the Church; and, lest we forget, women, who still experience discrimination so frequently but do not give up on the community. It is exactly to those people that we should look towards for guidance in efforts to co-create a better Church.

***

How do those people – and all of us – know that the Church is indeed fighting for? We know this because the faith upon which we build this Church is special. Our Catholic faith is rooted in the Gospel and what we learn from it is a story that inspires us to do better. This is a story of a God born in the periphery, in a poor family, in a shed where this family takes refuge when rejected by others. Christ then spends his life lifting up and healing the poor, the sick, and the rejected. In this way he helps all of us by teaching us that the essence of Christianity is love. He does reject, but he never rejects people, only the social order that marginalizes the poor, the hungry, and the sinful, all those who do not conform to social norms rooted in a sense of superiority. His death reveals a God who stands in solidarity with those suffering on the Earth. And his Resurrection promises us that death and evil can both be conquered.

This tale of salvation complements the Old Testament to provide us with a way of understanding and analyzing the world as Christians. We believe this way to be special and valuable not only as a tool for seeing, but also for changing our reality. To be a Christian is to respect the dignity and equality of every person: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). We are called to oppose indifference and act in defense of our sisters and brothers: “Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow” (Isaiah 1:17). The Holy Bible goes as far as readying us for a revolution when it urges us “to loose the chains of injustice and untie the cords of the yoke, to set the oppressed free and break every yoke . . . to share your food with the hungry and provide the poor wanderer with shelter – when you see the naked to clothe them, and not to turn away from your own flesh and blood” (Isaiah 58:6-7). Christianity is thus clearly emancipatory. And this forces us to analyze and to act simultaneously, to work towards transforming the social order and the structure underpinning it, and to individually care for every person in need. As Catholics, we must take action for social justice while never forgetting the needs of each individual – each person made in the image of God Himself. That is the dual and special mission of our community.

This mission requires us to think about the world in broad terms and seek justice by understanding the complexity and interconnectedness of all beings. This has consequences for so many issues affecting us today. For instance, Catholic teachings tell us that the Earth is God’s gift to all humans and thus none of us should accept the damage humanity inflicts on the environment nor the inequitable distribution of resources which are our common good. We also must stand with the poor and the hungry and welcome all those who need shelter, like those currently knocking on the locked gates of Fortress Europe. And while we try to address our collective problems, we should not forget about issues closer to our everyday lives. As Pope Francis pointed out, “Woe to you who exploit others and their work by evading taxes, not contributing to their pension funds, and not giving them paid vacation. Woe to you! . . . If you don’t pay, your injustice is a mortal sin.”

This is what Christianity in action means: caring both for social justice and for each and every fellow human. It is rooted in making forgiveness the rule of life and in love for God and for others. Even for those who disagree with us – “love your enemies,” Jesus told us (Matthew 5:44). His words may contain the hardest but the most important lesson that Christian teachings bring us, especially today, at the time when our societies are so bitterly divided.

All of this leads to a single conclusion. Christian teachings call us to continuously renew and improve our faith, to transform ourselves, the world, and our community. It is clear to us that this special emancipatory potential of Christianity, this promise of unique liberation it carries, is worth fighting for.

***

One can live by those values and principles while not part of the Church, or even while without faith. But it matters to us that our Catholic community was specifically called upon to promote those values and to show what living by them truly entails. And this mission does not even exhaust the vital meaning that the Church has. The Church is where we congregate together to meet God present in the sacraments, it is where we encounter Jesus Christ who we believe is more than a historical figure or a paragon of morality. Because of this faith, it is increasingly difficult for us to witness the sins of the Church. We are angry at how sin, both on the systemic and individual level, affects our Church, because this Church is not just an institution, but a living, holy community where mutual solidarity helps us overcome our weaknesses and act to make the world a better place. It is “a sign and an instrument both of a very closely knit community with God and of the unity of the whole human race” – as we learn from the “Lumen Gentium,” the Dogmatic Constitution issued by the Second Vatican Council. But we also should remember that, in the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “the Church is the Church only when it exists for others.”

Hence, we want to be a part of a Church that reaches into the periphery, that remembers the exploited and the marginalized, that asks, “where is your brother?” We believe in a Church that pushes us into action, that calls us to “get up from the sofa,” as Pope Francis put it. In this Church, we need more voices emphasizing truly Christian attitudes towards poverty, exclusion, refugeehood, and environmentalism. We need them all the more in the Polish Church, where such voices are particularly rare. Instead, Polish nationalists and libertarians, whose ideas stray far away from the Gospel, dominate the Church. We want to make sure that they do not win and that the Polish Church is truly Christian: that it stands in solidarity with the suffering of the Earth and fights for social justice.

We are trying to do our part in making the everyday life of the Church better, as we want to see each congregation become a supportive, participatory space wisely guided by priests who understand the problems affecting their communities. In this way we can build the Church we believe in, the “One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic” Church. Only then will this Body, the Head of which is Christ Himself, not be consumed by the diseases of power abuse, impunity, and indifference. We must do that because our Church simply has to cease being the source of pain and suffering.

We believe that another Church is possible. The crisis engulfing it makes clear that it is, in fact, necessary. That is why we remain part of this Church.

Translation: Karolina Partyga